Three Years a Lighting Designer

I have now been a theatre lighting designer for three years and… oooh… six months, give or take. I say ‘I have been’ but in my first secondment out of RADA a large part of the experience was being informed that to even call myself a lighting designer, in my ignorant state, was an offense to the profession, and I should consider myself brash to even consider myself a junior technician.

At the time, and given the manner in which this truth was addressed, I found it utterly disheartening. Three years later I do see its point.

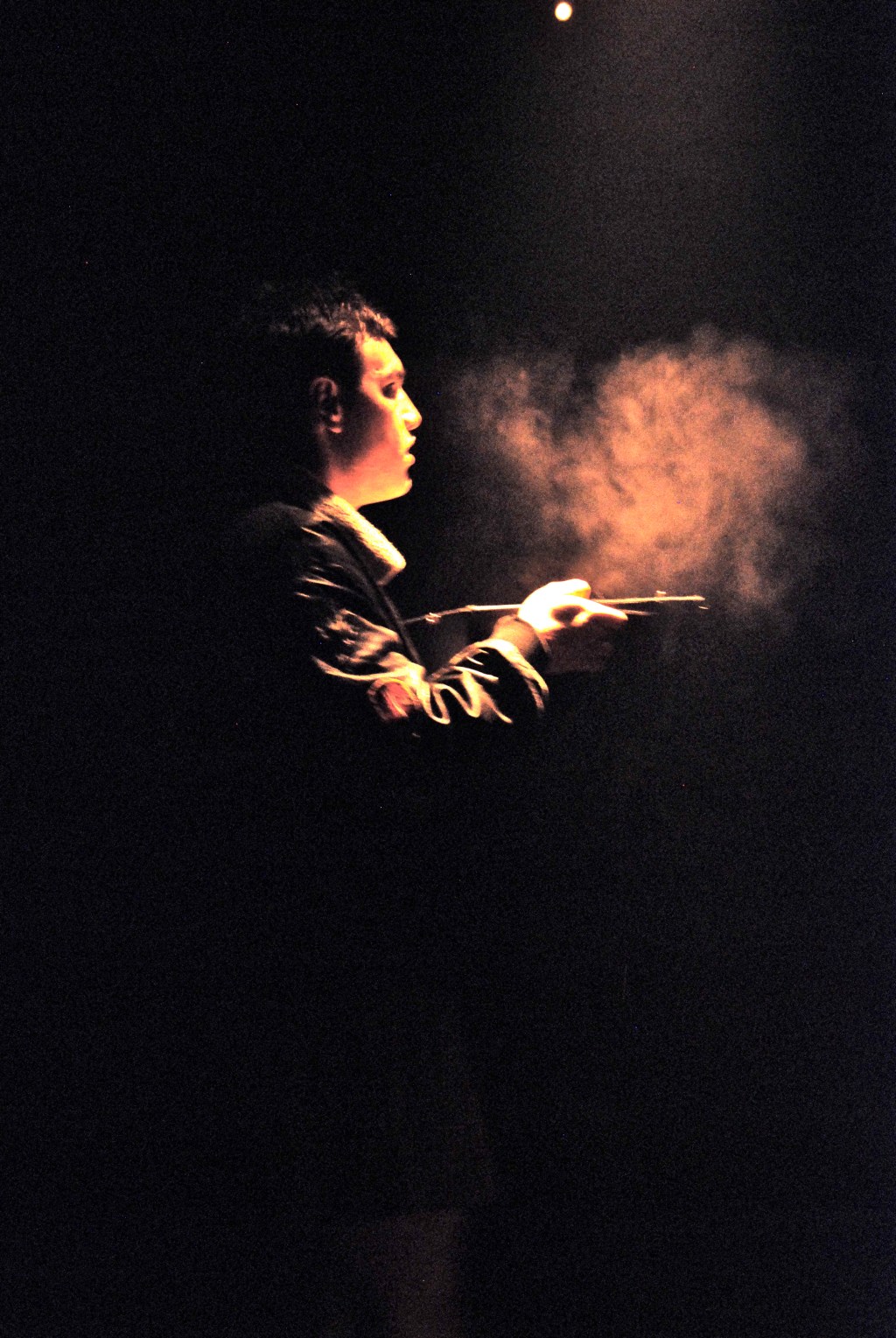

However, I’m going to take the plunge and say that finally I think I’m at that point where my calling myself an LD does no dishonour to the profession. I have lit dozens and dozens of shows, of every size and shape. I’ve fought against site-specific projects in spaces with no power, no equipment, no nothing save a dose of ambition; sat in techs in giant theatres surrounded by teaming crews and wondered just where in the 200-700 range of channels is the single unit I rigged to a ridiculously specific purpose amid the crowd of movers and generic lights. I’ve learned to program a whole range of desks with names that I fully intend, when I finally get round to writing space opera, to steal for the names of my planets, villains and spaceships. I’ve become a girl who lights music gigs, despite the fact that my knowledge of popular culture starts to get wobbly around about the treaty of Tsitsa-Torok. And I guess in the interest of being literal-minded about this, I’ve been accepted as Professional member of the Association of Lighting Designers, although alas the title didn’t come with a secret handshake. (Although if you ever meet me in a silly mood, ask me how lighting designers shake hands… I know a particularly nerdy joke along those lines…)

I find it hard to measure how my career is going. Secretly I keep an eye on the careers of a few of my contemporaries and attempt to roughly measure myself against their progress, use them as markers. I try my very best to do the best job I can on every show, regardless of its scale or fee, and still believe, with a few footnotes that I won’t bother with here, that meeting awesome people is the path to success. Every year I aim to work with someone new and someone I’ve worked with before, and stealing a lesson from one of the best lighting designers I’ve ever seen, Mark Howland, every show I try and do something new, whether it’s a new colour or a different choice of unit doing a different job, just to see if it works. Alas, on too many shows my rigging options and, more importantly, time, is often so limited that I have to stick with what I know just to get the job done… but sometimes there’s a chance to take a risk.

The book-thing is mostly a blessing in terms of my lighting design career. Simply put, most LDs after even three years in the job are struggling to earn a decent income without resorting to technician work to supplement their pay. While I’m a perfectly competent technician, one of the things I learned during my stint at the National Theatre was that I was never going to be a great one. Thankfully, I get to write books instead. On the downside, novel-writing doesn’t add to the theatrical contacts or technical experience I acquire, but on then again, I don’t have to write them while standing at the top of a ladder.

I always suspected that directors were a many-flavoured species, and three years have not diminished this view. I’ve worked with some incredible directors who, frankly, need to hurry up and take over British theatre as quickly as possible for the sake of all the awesome that must inevitably ensue. (Morphic graffiti… I look pointedly at you…) I’ve also done plenty of jobs where half of an LD’s job is finding a way to communicate ideas that make perfect sense in terms of lighting in the space, but are much harder to express to a creative team for whom ‘blue’ is the extent of their lighting vocabulary. What kind of ‘blue’ are we talking about? Daylight blue? Half CT blue? Royal blue, palace blue, congo blue, sky blue, ice blood, glacier blue, steel blue, deep blue, cyan, Tokyo blue? A blue to express a magical night, a blue to heighten a sense of loss, a jazzy blue, a sinister blue, a blue that really wants to be darkness but can’t quite pull it off, a blue indicative of a summer sky? Sometimes talking in a language other than filter colours can be a bit of an adventure for an LD, and as for explaining why something hugely technical cannot be achieved in plain language… it remains a long way from being fun…

I have, however, developed an extensive collection of cheese jokes. Technical theatre can be very stressful. It is almost invariably very tiring. Complicated sequences in a technical rehearsal can take hours, hours to rehearse. When I have a programmer, they tend to report that by day two the sound of my voice in their ear saying, ’37 at 50. At 45. Update to track. 101 into focus palette 7. Lift a little. Home beam. Update cue only…’ … has become ubiquitous enough to invade their dreams. After 48 hours of a tech, DSMs struggle to keep the tension from their voices as they growl down the intercom, ‘So when you say LX cue 271 is with ‘the shouty bit’ … could you be more specific?’

Consequently, I always go into technical rehearsals with cake, fruit, lots of water, and plenty of two-line jokes. I will fight for the things which I think are vital to the lighting design, but will also discard and add cues left, right and centre if I think it’ll achieve something more interesting than what I originally had in mind. As one of my favourite set designers points out whenever the set is falling down and the dimmer racks have tripped out… ‘Guys, it’s gonna be fine. Breathe out slow and work through the problem. We’re putting on a show here, not curing cancer.’ While this philosophy will never fix a broken shutter on a moving light, it is a healthy one to cling to whenever things look like they might explode, and it, along with the sacred mantra of ‘less is more’ pinned to my lighting console, is one of many many thoughts I try to take with me into a stressful plotting session.