Cyphers

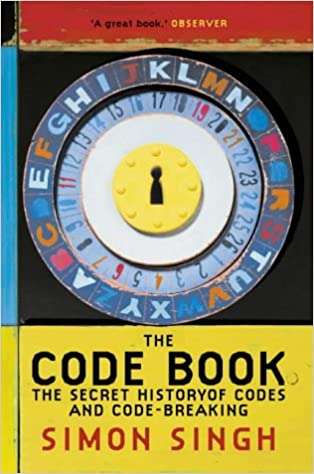

I’ve just finished reading an awesome book. (I usually hate the word ‘awesome’ as it’s been mis-used too much lately, but just this once, I think the book in question merits it.) It’s The Code Book, by Simon Singh, and is, as you might guess, a romp through the history of cryptography.

Now…

… it’s not every day that I go off and praise books on cryptography, because, you know, it doesn’t really fit in with the fantasy-writer-street-cred thing. But then, I’ve had a vague interest in codes for years. As regular readers will know, I keep diaries, and have done in a slightly neurotic way since I was about twelve. It’s not a day-by-day thing, merely an important-stuff-happened-here thing, and I’ve always viewed my diaries as the literary equivalent of a wall to bang my head against. However, as they are personal, and contain so much of my life, at a fairly early age I wanted some way to protect them. Since I am guaranteed to lose any key on any lock which might lock away a notebook, I started using a crude substitution code to protect my writings. Initially I learnt the Russian alphabet, substituting the Russian symbol for a letter for the English. Once I’d got the hang of that, a friend taught me the ancient Greek alphabet – which is pretty much the granddaddy of the Russian anyway – and I was able to start adding more symbols to my vocabulary, mixing up Greek and Russian to create my code. The benefit of course being that I could now not only write my diary in reasonable security on the Piccadilly Line, but also keep my own notes in class…

In Greek, there are a couple of letters which are actually compound syllables, such as ‘theta’ – which we’d write today as ‘th’. From this, the next part of my code started happening, and I began using compound syllables such as ‘gh’, ‘ed’, ‘ing’ and variations on common endings such as (vowel)-nt or (vowel)-rt. It sped up writing my code, and added an extra layer of security, in the sense that once you know how, reading the Russian alphabet really isn’t hard at all. Around about the age of 17, I learned the Arabic alphabet, simply because I thought it looked very beautiful, and I still use it now sometimes for keeping my diary. I haven’t integrated it with my initial code, simply because I couldn’t work out how, but find that the simple act of writing in a different alphabet, can actually change the content. With my Russian-Greek code, it’s easy to write quick thoughts and brisk notes. With Arabic, I find the movement of the letters actually creates a slower, more thoughtful writing style, and so I switch between alphabets largely dependent on context and how tired I am at the time.

By the time I was 18, common words had acquired symbols as well. ‘The’, ‘and’, ‘you’, ‘I’, ‘things’, ‘where’ ,’when’, ‘what’, ‘why’, ‘not’ and so on and so forth all have their own symbols. Interestingly, so does ‘anyway’ which tells you a fair deal about my natural diary style. Aged 22, I went on holiday to South Korea, and learned the Korean alphabet as well. Interestingly, the Korean alphabet was designed for maximum ease of learning, and utility within the confines of the Korean language – it’s a very modern alphabet, one of the few tailor-made by scholars for an already existing language. However, it soon became apparent that while Korean was very good for writing Korean (there’s a shock) it’s actually a bit clunky for using as a substitute code in English, so I went back to what I knew. On a summer holiday in the library, I also learned the Bangla alphabet, but again, found the shapes of the letters and the way they joined up, a little unwieldy in English, and that particular bit of knowledge has, I think, faded fairly quickly from my brain.

All of which brings me back to cyphers. I’m rubbish at languages, but have always enjoyed codes. Cracking a simple substitution code is something I do for fun on the underground, when I’ve reached such mental rock-bottom that my brain’s good for nothing else – sort of my preferred equivalent to sudoku. I do find it easier to crack a code when I’m looking at letters, rather than numbers, simply because I find it easier to spot patterns in terms of layout. But now that I’ve read The Code Book, I’m naively hoping to expand my interest, and start looking at more difficult codes. Modern technology has giving us the ability to create near-impenetrable codes – certainly, impenetrable to anything less than the most powerful computers in the world – but for hundreds of years codemakers and codebreakers danced around each other using nothing but ingenuity and hard work to try to protect and break layers of privacy, and to this day, the brilliance of their wits and the intelligence they deployed, are both exciting to observe, and a challenge to unfold.